Freight News:

Maritime History Notes: Ships of concrete

FreightWaves Classics is sponsored by Old Dominion Freight Line — Helping the World Keep Promises. Learn more here.

The first concrete vessel was a rowboat built in 1848.

Frenchman J.L. Lambot at the time constructed a series of rowboats using a procedure he called “Fericement.” Fericement is a forerunner of what is known today as ferro-cement. This is because steel rods are used to form a wire mesh that creates a skeleton of the ship’s hull, over which concrete is poured to form the hull.

It is important to note that concrete is made by mixing cement, sand and water. Thus, we cannot say a vessel is cement, but concrete. Incidentally one of Lambot’s rowboats is still afloat in the Netherlands.

The first practical seagoing ship of concrete was the 84-foot motorship Namsenfjord, which was designed and built by Norwegian shipbuilder N.K. Fougner. He began with the construction of concrete lighters (barges) based on a 1912 patent. The Namsenfjord was completed in 1917 and approved by classification societies that same year.

The entrance of the U.S. into World War I and the heavy loss of shipping through submarine warfare precipitated the U.S. Shipping Board’s embarking on a large-scale steel shipbuilding program. Due to a shortage of steel and the fact that a hull made of concrete requires about a third less steel per deadweight ton compared to a steel ship, concrete ships became important to the war effort.

At this time, San Francisco businessman L. Comyn, who recognized the futility of building wooden ships from green lumber and the general lack of shipyard proximity to steel plants, proposed building vessels with concrete hulls to the U.S. Shipping Board.

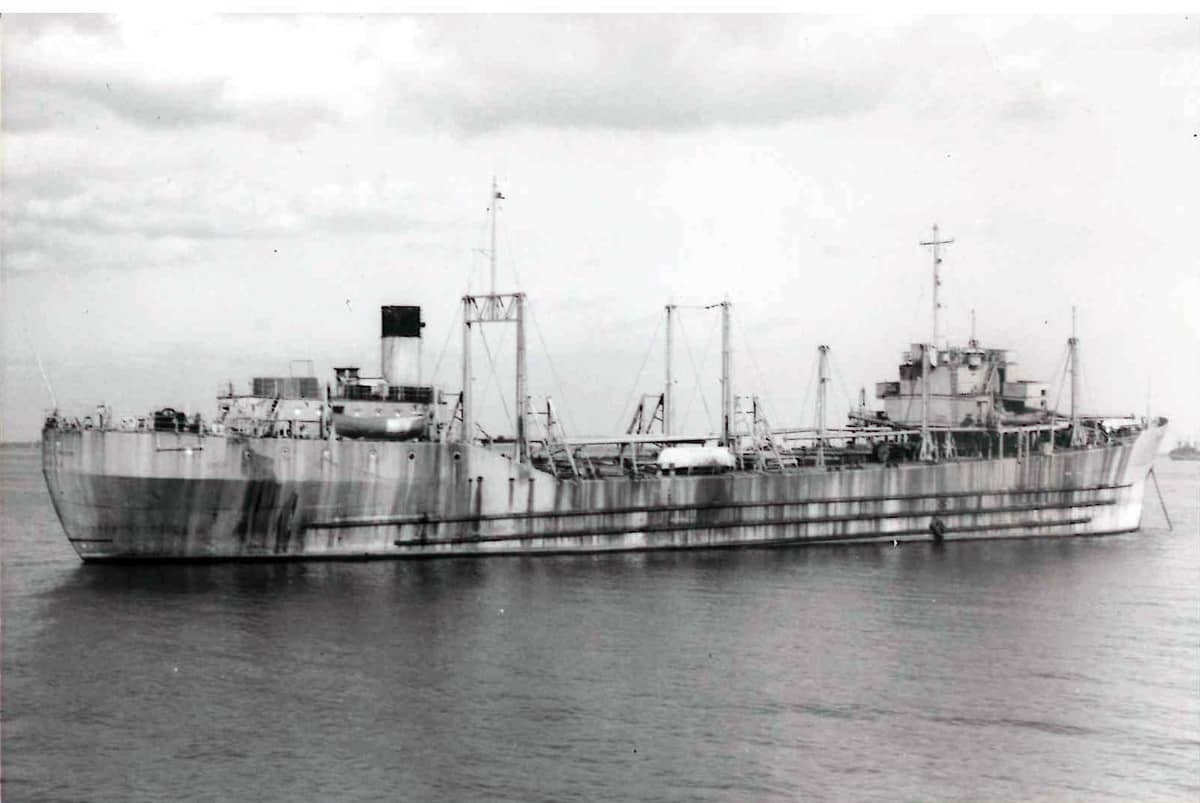

Seeing little interest from the federal government, Comyn established the San Francisco Shipbuilding Co. at Redwood City, California. In September 1917, he started construction and by March 1918, the steamship Faith was christened. At the time, it was the largest concrete ship in the world and the first built in America. The Faith was a single screw steamer of 3,427 gross tons. The triple expansion engines powered the ship to 10 knots.

San Francisco Shipbuilding used deformed bars provided with lugs to obtain the optimal bond between steel and concrete. The side and bottom slabs were 4 to 4.5 inches thick, reinforced diagonally; the shelter deck slabs were 3 to 3.5 inches thick and there were seven watertight bulkheads of concrete. Poop, bridge, forecastle and main decks, however, were constructed of wood, as were the ceilings of the cargo holds. The steamer’s hull was rather blunt. At the time, it cost the shipyard $750,000 to build the Faith.

The U.S. Shipping Board took notice and decided to build 38 concrete ships. Only 12 were completed. The first two, both 2,450 deadweight tons in size, were built on an experimental basis — one at North Beach, New York, and the other at Brunswick, Georgia. Both were delivered in 1919.

The remaining 10 ships were built by the Emergency Fleet Corp. with shipyards at Wilmington, North Carolina; Mobile, Alabama; San Diego and Oakland, California; and Jacksonville, Florida. Eight were completed as 7,500-ton tankers by the shipyard.

These ships did not sail long, since there was a glut of tonnage after the war and being of heavy construction were not economical to operate. Most of these concrete ships were utilized as breakwaters or piers by the early 1920s.

Over the next 20 years, only three concrete tankers of 298 feet long were built for the France and Canada Oil Transport Co.

After the dismal deployment of concrete steamers during the First World War, most U.S. shipyards during World War II shied away from using concrete hull construction despite the renewed shortage of steel.

In 1942, a shipyard at Hookers Point in Tampa, Florida, was tasked by the U.S. government to build 24 concrete dry-bulk ships to transport sugar. These vessels, with their six cargo holds, measured 350 feet in length, 54 feet in beam and 35 feet in depth. Their concrete sides were 6.5 inches thick with four layers of reinforcing steel. The ships were easily identified by three rows of wooden fenders on their sides.

All 24 of these concrete ships bore the names of prominent individuals of the cement industry. The first of the fleet was the David O. Saylor, which was delivered in November1942 to Lykes Bros. Steamship Co. of New Orleans.

The remaining ships, although owned by the U.S. government, were operated by other commercial steamship companies for a period before being acquired by the Army for use as store ships or training ships in the South Pacific during the war.

By 1950, all 24 concrete ships were either scrapped or sunk as breakwaters at Kiptopeke, Virginia; Newport, Oregon; and Powell River, Canada.

Of the approximately 50 concrete ships built in the U.S. during the past century, the Faith was the most commercially successful, with three years in service. The ship sailed the Pacific, Mediterranean and Atlantic before it became a breakwater in Cuba during 1922.

But that was not the final story for ferroconcrete ship construction. In fact, numerous small vessels, barges and yachts today continue to be built with concrete. Additionally, prestressed and pretensioned concrete construction has been extensively utilized in pontoon bridges, offshore petroleum production and storage facilities.

Click for more Maritime History Notes articles by Capt. James McNamara.

The post Maritime History Notes: Ships of concrete appeared first on FreightWaves.

Source: freightwaves - Maritime History Notes: Ships of concrete

Editor: Captain James McNamara, contributor