Freight News:

Can the minnows pick up the slack if the brown whale is beached?

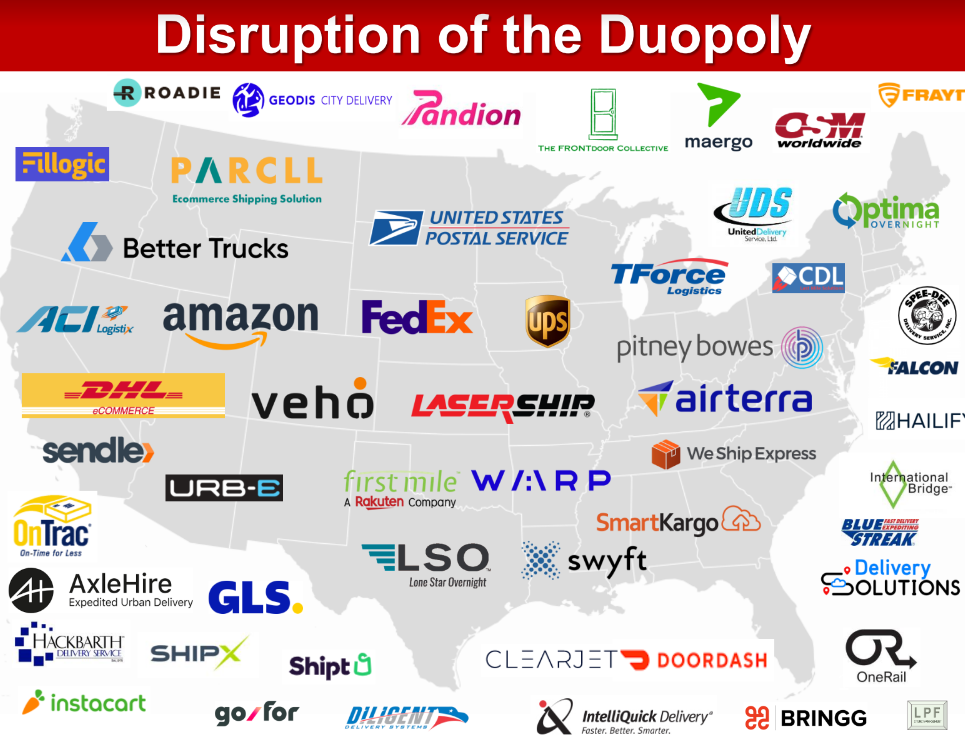

As the chart shown below indicates, there is no shortage of parcel-delivery companies in America. There are certainly far more than in 2018, the last year that UPS Inc. and the Teamsters union negotiated a collective bargaining agreement.

That contract expires July 31, and there is concern among parcel consultants that UPS shippers are taking the upcoming deadline too lightly to be actively looking for alternative capacity. Few expect a strike because all stakeholders have so much to lose. But UPS shippers are advised not to take any chances, especially as the Teamsters have more bargaining power than they’ve had in years.

UPS (NYSE: UPS) moves more than 20 million daily packages in the U.S. alone. These volumes would swamp even the more established carriers. The many smaller carriers that have sprung up in recent years lack the scale to effectively manage volume spikes if a carrier that delivers about half of all U.S. volumes is either shut down or its network is curtailed, according to industry experts.

This shouldn’t keep UPS shippers from looking around. The question is when.

“Shippers don’t seem to be taking the possibility of a UPS strike all that seriously — yet. Few think UPS will actually strike, but the logistics manager’s job is to have a contingency plan in place,” said Rob Martinez, founder and co-CEO of consultancy Shipware LLC. “Shippers told us back in September 2022 that they’d begin to explore alternatives to UPS in January 2023. But that didn’t materialize.”

“Shippers are making a mistake if they aren’t now looking around for alternate capacity,” said Joe Wilkinson, head of professional services for Intelligent Audit. “It’s getting late if you’re not doing anything now.” For example, FedEx Corp. (NYSE: FDX) is telling UPS shippers to “get in now or don’t get in,” Wilkinson said.

“Customers are coming to us, and there’s a lot of anxiety in the market for sure,” said Shankar Natarajan, president of Quiet Platforms, which has stitched together first-mile, middle-mile and last-mile delivery services using 40 different carriers.

Natarajan said that Quiet could scale quickly to handle delivery surges. “We went from zero to 50 million packages a year in nine months,” he said.

As of early February, most alternate delivery firms appear to be fairly wide open. For example, LaserShip OnTrac, the largest regional carrier in the country, has plenty of capacity after a $100 million build-out in 2022 that included a new hub outside Philadelphia and expansions of hubs in Columbus, Ohio; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Nashville, Tennessee.

A source close to the company said it expects to be able to accept new shippers as late as September, one month after the UPS contract expires. “If there is a strike and people come to us at that time in August, we will be respectful to our existing customers. However, we will be working full bore to bring on new business through September,” the source said.

Abundant capacity isn’t likely to last very long, though. Space nationwide is expected to be filled up by mid-June, according to Martinez. The only way such a timetable would change is in the unlikely event UPS and the Teamsters jointly and publicly announce significant progress in negotiations and minimize the threat of a strike, he said.

As the summer draws near with no clear movement toward a settlement, regional carriers will experience a boost in volume commitments, Martinez said. However, the regionals have put shippers on notice that they will not be transactional, he said. UPS shippers must commit to a relationship and not just use the regionals as a safety valve in case there is a strike, only to return to UPS once it ends.

How this plays out depends on UPS’ behavior. The company apparently plans to keep operating in the event of a strike. It has notified managers not to take paid time off days in July and August in case they are needed to move packages. No one expects UPS to operate at full capacity if a work stoppage occurs. The key to minimizing service disruptions, Wilkinson said, is whether the carrier runs at 80% capacity, 60% capacity or some other percentage. “That number matters,” he said.

John Haber, chief strategy officer of Transportation Insight Holding Co., a consultancy, said that all the regional and national carriers are leveraging the possibility of a strike in order to push up volume commitments into early 2023. But things will get tight even if there isn’t a strike because of an ongoing labor shortage, Haber said.

Regional carriers, which have long held a single-digit percentage share of the domestic parcel market, have seen their share grow partly because of a surge in delivery volumes, and partly because FedEx and UPS have ratcheted rates and surcharges up so high that it has alienated many longtime shippers and forced them to look elsewhere.

Still, regionals typically do not offer the same value proposition as UPS or FedEx, according to Martinez. Many shippers would rather work with one carrier than with many, he said. Regional carriers don’t have the geographic footprint of the national carriers. Somewhat surprisingly given their lower cost to serve, regionals occasionally can’t beat the nationals on pricing, Martinez said.

Another factor keeping shippers from shifting volumes to regional is that they stand to lose their price discounts from UPS and FedEx, according to Martinez. The carriers set their discounts based on specific volume thresholds. Discounts can be forfeited if volumes fall below any of those thresholds.

The post Can the minnows pick up the slack if the brown whale is beached? appeared first on FreightWaves.

Source: freightwaves - Can the minnows pick up the slack if the brown whale is beached?

Editor: Mark Solomon